In this issue…

What’s this greenhouse malarkey anyway?

A long overdue writing update from me

Interview with linguist Dr Lauren Gawne about Shadowscent, language and plants

What’s The Greenhouse all about?

Hi there!

Thank you for joining me for the very first edition of The Greenhouse with P. M. Freestone, a monthly newsletter about growing plants, stories and ideas.

It feels apt to begin this journey in April. Here in Scotland, the spring equinox arrives in March. But April is the month where something shifts. Last year, I kept a journal of gardening and writing thoughts, which was part of the inspiration for The Greenhouse. Looking back on those pages, there’s a palpable sense of starting April in wintry doom (and, as an Australian in these northern climes, with lingering S.A.D.), then emerging in its final days with a sense of hope:

It’s unseasonably cold. Even for Scotland. It’s also unseasonably dry. Especially for Scotland. The combination is lethal for many plants. New spring growth gets burned and dies back in the scything wind. Cracks appear in the clay soil. There’s no point hardening off any seedlings. No point sowing any seeds outdoors. But the ticks (carrying Lyme) emerge in swarms, the ants build nest after nest, and the wasps are back and aggressive – as if they’re angry this is what they’ve woken to. My partner keeps saying ‘April is the cruellest month…’ and I (somewhat waspishly myself) retort that quoting Eliot isn’t helpful right now.

I’m rather a grump until the early tulips finally appear towards April’s end and put a smile on my face. I didn’t get the colour combos quite right when planting them, but I’m still pleased. I’ve never had great swathes of tulips in a garden before. It’s a decadent luxury that lifts the month’s otherwise desolate mood.

For me, The Greenhouse is like the tulips at April’s end. A reliable moment of glorious luxury to revel in nerdy things. Most of my other projects are relatively isolated pursuits with much longer lead times. The Greenhouse is a chance to share in the spaces between.

Each month, I’ll take you behind-the-scenes of my research and writing process, share a bunch of cool stuff I find along the way (including peeks into my garden), and interview interesting people about how they grow plants, stories and ideas.

Sound like your thing?

Welcome to The Greenhouse with P.M. Freestone.

An update: growing plants, stories and ideas

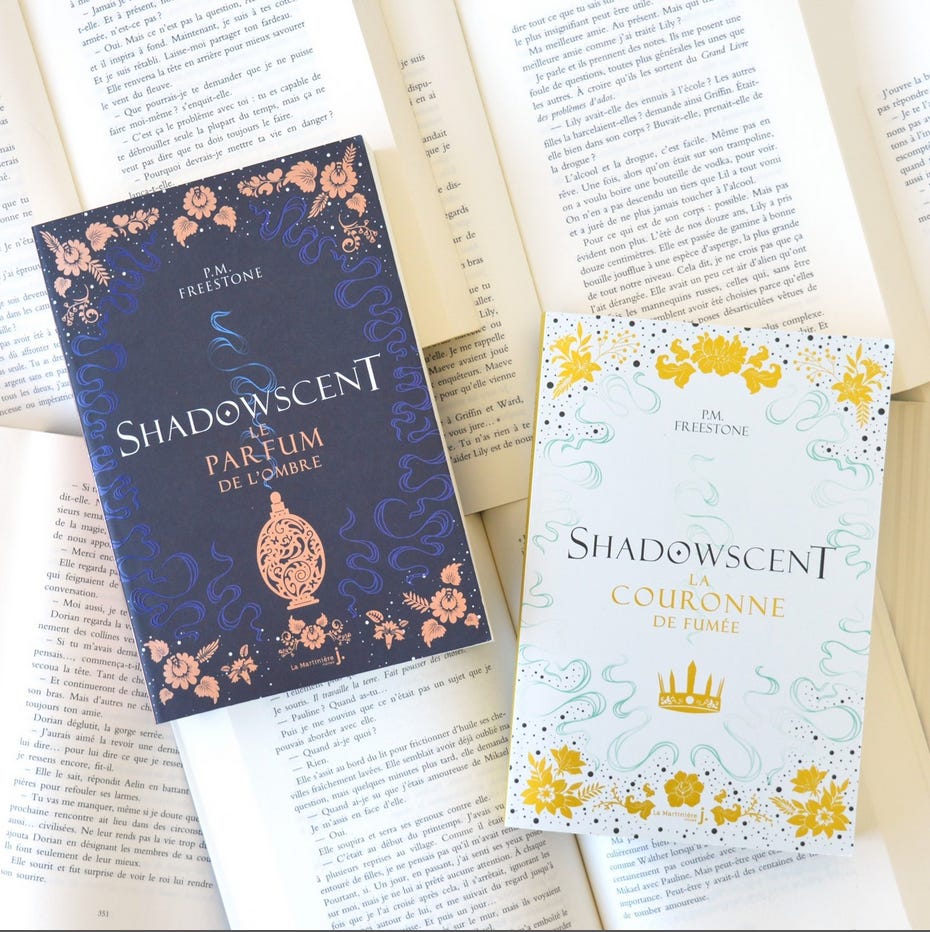

Shadowscent: Crown of Smoke was first published in April 2020, with the translations releasing over the following year. In the lead up, I was preparing to head around the UK and beyond to chat to wonderful readers.

We all know what happened instead.

Not long after, I was fortunate to realise a long time ambition to move out of my inner-city apartment to a village and a dilapidated fixer-upper renovator’s dream with a yard. As many of us have done since 2020, I spent as much time as possible outdoors. I threw myself into creating a garden from a patch of ground that had been neglected for thirty years. Luckily for me, there’s nothing like sinking my hands into the soil or raising a plant from seed to heal body and mind.

Then, about a year ago, I embarked upon another big change. I was appointed as a Lecturer at Edinburgh Napier University to research and teach in creative writing. It’s a part time role, so I’m still able to spend a couple of days a week squirreled away in my garden office at home, developing my craft and thinking deeply about the kinds of stories I most want to tell during this one precious life. I’ve allowed myself space (another tulip-like luxury) to experiment across genres and age ranges, working solo and collaboratively. I’m looking forward to sharing beyond my wonderful network of author friends soon. Keep everything crossed!

In the meantime, I’ve been busily interviewing interesting folk for The Greenhouse. This month’s guest brings me full circle. I’m looking back to the research behind the worldbuilding for the Shadowscent books, which are set in a fantasy world where life revolves around the sense of smell. Plants have always been a feature in my work—perhaps no more so than in Shadowscent’s Aramtesh Empire, where flowers and herbs produce some of the most valuable commodities: perfume. I hope you enjoy reading as much as I enjoyed chatting with my guest!

Talking Shadowscent, language and plants with Dr Lauren Gawne

Lauren is the linguistics expert who helped me create the language and associated worldbuilding in the Shadowscent duology. Here’s a broader intro to their work:

Lauren (she/they) runs Superlinguo, a blog about language and linguistics, and Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics (co-hosted with Gretchen McCulloch). Lauren’s also a Senior Lecturer at La Trobe University (Australia), documenting and analysing how people speak and gesture. Lauren focuses on evidentiality and gesture, with a particular focus on cross-cultural gesture use, and the grammar of Tibetan languages in Nepal. Finally, Lauren researches emoji, constructed languages, and the role of data in linguistic research.

PM: Whew! Just reading about all that makes me thankful you could spare the time to chat today—welcome to The Greenhouse!

LG: I’m happy to be here!

I’m still so grateful for your work developing Aramteskan, the language for Shadowscent. Imagining a world where smell was queen of the senses was a challenge. When I first started planning the books, I went to the National Poetry Library here in Scotland, and asked for ‘all the poetry about smells’. The librarians thought it a delightful question, as there was no easy answer. So I trawled through food poetry, garden poetry and the works of perfume writers (including Sarah McCartney of 4160Tuesdays who created the dahkai perfume of my dreams). You weren’t surprised by there being less of a literary tradition around smell, were you?

Not at all. Our sense of smell is relegated to being less of a focus than our other senses like sound and sight. That's reflected in our cultural priorities, but it's also reflected in the fact that we have a relatively impoverished grammar for talking about smell. In English, you quickly run out of different verbs to describe the act of smelling. We also have so many more negative words for things that smell strongly than positive words for things that smell strongly.

English speakers and speakers of European languages also tend to use the word that the thing smells like to describe the smell. One cross-cultural study compared smell words between Dutch, Thai and Maniq (spoken in Thailand) speakers. People who speak the latter two of those languages had a larger vocabulary of abstract smell terms they could use to describe smells, and would more readily use them, whereas the Dutch speakers have to reach around the edges of their language.

When we were creating the Aramteskan language for the Shadowscent books, we put a lot of emphasis on making sure that a language in a world where scent was the priority was well reflected in the richness of its vocabulary. It became a fun creative exercise—thinking about all the different ways that we, as humans, interact with scent. I hope that process provided a source of inspiration when you were trying to translate that experience into English for the reader.

It certainly did! I still think about this process now that I’m researching plants (and their seemingly low priority) in literature as part of my role as a Lecturer in Creative Writing at Edinburgh Napier University. I’m wondering if the linguistic situation with scent in English might be similar to the way we treat plants in our written stories?

In some ways we get in the habit of paying attention to what our languages, grammar and vocabulary gives us the easy tools to pay attention to. Thinking about this in terms of plants, did you know Ojibwe has two different plural markers? They have a plural for animate things and a plural for non-animate things. Plants are generally (but not always) included with animals and people as animate things, and you get two different plural forms. It's cool, it means your grammar is making you pay attention to the living world in a different way to English.

Nicholas Evans has this lovely example about the interconnectedness of living things in his book on endangered languages: Dying Words. In Arnhem Land in the north of Australia, what we know in English as the spangled grunter fish and the native white apple tree (Syzygium eucalyptoides) bear the same name in Kunwinjku: bokorn. They have the same name because the fish eats the fruit that falls from the tree. Having grown up speaking this language, you could potentially think ‘I’d never thought about that plant in that way before’, but the chances are obviously greatly reduced. It’s a very different way to see the relationship between plants and the world.

That’s so interesting. In European traditions, we have some wonderfully rich folklore and associated names for plants. But we now often reify the Linnaean system—classifying the natural world in evolutionary relationships and giving living things Latin names. It can make plant knowledge feel elitist—not many people have the resources (money, time, access) or inclination to learn Latin. Plus, many Latin plant names still reflect their colonial roots—plant hunters (mostly white men) who went to a bunch of places where plants already had local names and renamed their botanical ‘discoveries’, often after… themselves.

The thing about the Linnaean system is that, in choosing Latin, you abstract away a lot of the knowledge. We’re all going around saying things like ‘this is the native white apple tree’ but if we say it in Latin, we make it opaque, so that it sounds smarter but it’s not necessarily more useful.

That’s the exclusionary aim of elitism isn't it? What's more powerful than controlling knowledge about the things—plants—that the entire world relies on to survive, human and animal?

So much of the world's botanical knowledge is held in the minds of people who speak some of the 6,000 endangered languages in the world. There's been a lot of noise made about the importance of preserving these languages so we can preserve this knowledge. I absolutely agree with that. I’m somewhat wary when we say this is important because one of them might have the next cancer cure in a plant we've yet to medically understand. That approach reduces the richness of the diversity of knowledge about plants (their function, use and their very existence) to try to communicate something of commercial value. I wish we had more respect for understanding and approaching this knowledge for its intrinsic value.

Value is a good word for what I’m thinking about next – I’d love to know what role plants have in your life?

For me, paying attention to plants is the best way to stay temporally grounded. I have a series of walks around my neighbourhood I like to do regularly. I know where the good smelling roses are (because I’ve leaned over people's fences!), and this month I’m learning where all the mock orange is hidden and am enjoying that greatly. I’m constantly being delighted and surprised by a tree I paid no attention to three months ago suddenly having pomegranates. Or, the other day, I finally learned what a crepe myrtle is—I’ve walked these Melbourne neighbourhoods for decades and never paid attention to this tree that really captivated me and then made the footpath turn pink with blossom.

The constant shifting of the plants and the seasons is also a good reminder that the seasons we do have are artificially imposed from European climes into Australia. They don’t quite fit. An illustration of this can be found in the interactive map on Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology website, which highlights indigenous weather knowledge. In my home state of Victoria, you see six different seasons that relate to flowers and birds and animals that are active in those seasons—the honeybee season, the eel season. It makes much more sense.

I suppose I also take note because my grandparents had an amazing garden when I was growing up. I learnt that apricots happen just after Christmas, and get you through early January. Plums are February and are the thing to go and steal from the garden after the school year starts. My parents had a small apple tree that had early winter fruit. I’ve realised that I take this amount of knowledge for granted. And this knowledge prompts me to take notice of other things that my family didn’t grow. I pay attention in the supermarket to secondary indexes like price and quality. I feel some fruit shouldn't be available to me whenever I want. There is actually a greater joy in celebrating local cherry season, and then when cherry season passes knowing that you're only a few months away from local grape season. There’s no linguistic insight there, just a stubborn belief in the importance of de-industrializing our food production system for greater sustainability and reduced waste.

In my own little space, I like growing chilli plants every year, and lots of herbs. I’m selfishly happy to be indulging in other people's beautiful flowers and ornamentals, but at home the little energy I have for gardening means plants need to be hardy or useful. In the case of my mint… both!

I hope you keep that mint in a pot, the unconquerable, spreading hero it is! And if you had to pick a favourite plant?

Jasmine. It became grounded in my annual calendar in my undergraduate days. Jasmine would kick off just as spring was really asserting itself. You knew you were sliding into the end of the academic year and things started to feel promising. Wherever I lived, across various share-houses and suburbs, I’d find the back alleys (which might sound terrifying in other cities but is a completely legitimate exercise in Melbourne) where the jasmine would grow. It is one of the few plants that I will actively attend to outside of season so that I know where to head back to when it is time for it to bloom.

As someone who also grew up with Melbourne’s jasmine back alleys, I agree, it’s a very hopeful scent. In Shadowscent, I made it ‘melbon’ (as close as you get to ‘Melbourne’ in Aramteskan) in your honour. It’s the first scent Rakel gets back after she loses her sense of smell at the end of Book 2.

I lost my mind the first time I read that! I was deeply touched and also delightfully impressed that you had completely mastered the phonetics of Aramteskan to be able to say Melbourne jasmine.

Why, thank you! And one last thing – what’s your favourite book that features plants?

Science fiction is a great place to explore sentience and the interconnectedness of the natural world. I love Sue Burke’s Semiosis and Interference for asking questions about what it means for plants to be sentient and how they might interact with human intelligence… on another planet.

I loved those books! And I love that you gave some of your precious time to talk about plants, stories and ideas with me today. Thank you so much!

In the next issue of The Greenhouse…

Tropical rainforest and poison gardens with a New York Times bestselling crime author.

Don’t miss it!

Palm photo by Valentin BEAUVAIS on Unsplash